Международный эндокринологический журнал Том 19, №6, 2023

Вернуться к номеру

Патогенез діабетичного макулярного набряку: роль гліального компонента (огляд літератури та власні дані)

Авторы: Кирилюк М.Л. (1, 2), Сук С.А. (3)

(1) — ТОВ «Академічний медичний центр», м. Київ, Україна

(2) — Харківський національний медичний університет, м. Харків, Україна

(3) — Центр мікрохірургії ока, Київська міська клінічна офтальмологічна лікарня МОЗ України, м. Київ, Україна

Рубрики: Эндокринология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

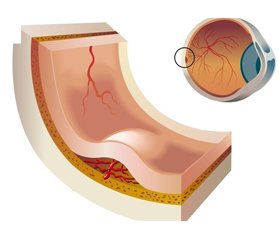

В огляді наведено сучасні дані щодо патогенезу діабетичного макулярного набряку. На сьогодні нове розуміння патофізіології діабетичних уражень сітківки ока включає структурну дисфункцію нейросудинної одиниці сітківки ока. Нейросудинна одиниця включає астроцити й клітини Мюллера, забезпечує фізичний і біохімічний зв’язок між нейронами, глією, судинною мережею in situ, є межею розділу між нейронами і судинною системою і ключовим регулятором нейронного метаболізму. Тісна взаємозалежність гліальних клітин, перицитів і нейронів сприяє формуванню бар’єра між кров’ю і сітківкою, який контролює потік рідини і гемотрансмісивних метаболітів у гліальну паренхіму тканини ока. Гліальні компоненти нейросудинної одиниці сприяють виживанню нейрональних гангліозних клітин і фоторецепторів, стабілізації структури сітківки і модуляції запальних та імунних реакцій. Показано, що міжклітинні взаємодії між кровоносними судинами і нейронами відіграють критичну роль у формуванні гематоретинального бар’єра, функція якого модулюється станом ретинальних ендотеліальних комунікацій. При цукровому діабеті гематоретинальний бар’єр розщеплюється вже на ранній стадії діабетичної ретинопатії, змінюючи структуру і функцію більшості типів клітин у сітківці, проте молекулярні механізми цього патологічного процесу при цукровому діабеті вивчені недостатньо і потребують пошуку нових терапевтичних стратегій, зокрема за участі кластерину. Вказано на значущість дисфункції нейросудинної одиниці сітківки ока в розвитку ускладнень цукрового діабету. Підвищена увага надається мікрогліальній активації, дисфункції клітин Мюллера, ураженню гематоретинального бар’єра при цукровому діабеті, а також ролі клаcтерину й фракталкіну в бар’єрній цитопротекції.

The review presents modern data on the pathogenesis of diabetic macular edema. Today, a new understanding of the pathophysiology of diabetic retinal lesions includes structural dysfunction of the neurovascular unit (NVU) of the retina. NVU includes astrocytes and Müller cells, it is a physical and biochemical link between neurons, glia, vascular network in situ, acts as an interface between neurons and the vascular system, and is a key regulator of neuronal metabolism. The close interdependence of glial cells, pericytes and neurons contributes to the formation of a barrier between the blood and the retina, which controls the flow of fluid and hemotransmissive metabolites into the glial parenchyma of eye tissue. Glial components of NVU contribute to the survival of neuronal ganglion cells and photoreceptors, stabilization of the retinal structure, and modulation of inflammatory and immune reactions. It has been shown that intercellular interactions between blood vessels and neurons play a critical role in the formation of blood-retinal barrier whose activity is modulated by the state of retinal endothelial communications. In diabetes, the blood-retinal barrier breaks down already at the early stage of diabetic retinopathy, changing the structure and function of most types of cells in the retina; however, the molecular mechanisms of this pathological process in diabetes are not sufficiently studied and require the search for new therapeutic strategies, in particular, with the participation of clusterin. Emphasis is placed on the significance of dysfunction in the neurovascular unit of the retina for the development of complications in diabetes. Increased attention is paid to microglial activation, Müller cell dysfunction, damage to the blood-retinal barrier, as well as the role of clusterin and fractalkine in barrier cytoprotection.

діабетичний макулярний набряк; патогенез; огляд

diabetic macular edema; pathogenesis; review

Для ознакомления с полным содержанием статьи необходимо оформить подписку на журнал.

- Antonetti D.A., Klein R., Gardner W.T. Diabetic Retinopathy N. Engl. J. Med. 2012. 366. 1227-1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005073.

- Hawkins B.T., Davis T.P. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005. 57. 173-185. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.4.

- Pournaras C.J., Rungger-Brandle E., Riva C.E., Hardarson S.H., Stefansson E. Regulation of retinal blood flow in health and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2008. 27. 284-330. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.02.002.

- Ascaso F.J., Huerva V., Grzybowski A. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of macular edema secondary to retinal vascular diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2014. 2014. 432685. doi: 10.1155/2014/432685.

- Lee S.W., Kim W.J., Choi Y.K. SSeCKS regulates angiogenesis and tight junction formation in blood-brain barrier. Nat. Med. 2003. 9. 900-906. doi: 10.1038/nm889.

- Choi Y.K., Kim J.H., Kim W.J. AKAP12 regulates human blood-retinal barrier formation by donregulation of hypoxia-indu–cible factor-1alpha. J. Neurosci. 2007. 27. 4472-4481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5368-06.2007.

- Kim H.-J., Yoo E.-K., Kim J.-Y. et al. Protective role of clusterin/apolipoprotein J against neointimal hyperplasia via antiprolife–rative effect on vascular smooth muscle cells and cytoprotective effect on endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009. 29(10). 1558-1564. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.190058.

- Cunha-Vaz J., Bernardes R., Lobo C. Blood-retinal barrier. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2011. 21(6). S3-S9. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2010.6049.

- Lorenzi M., Gerhardinger C. Early cellular and molecular changes induced by diabetes in the retina. Diabetologia. 2001. 44. 791-804. doi: 10.1007/s001250100544.

- Antonetti D.A., Barber A.J., Bronson S.K. et al. JDRF Diabetic Retinopathy Center Group. Diabetic retinopathy: seeing beyond glucose-induced microvascular disease. Diabetes. 2006. 55. 2401-2411. doi: 10.2337/db05-1635.

- Zhang C., Nie J., Feng L. et al. The emerging roles of clusterin in reduction of both blood retina barrier breakdown and neural retina damage in diabetic retinopathy. Discov. Med. 2016 Apr. 21(116). 227-37. PMID: 27232509.

- De Silva H.V., Harmony J.A., Stuart W.D. et al. Apolipoprotein J: structure and tissue distribution. Biochemistry. 1990. 29(22). 5380-538. doi: 10.1021/bi00474a025.

- Wong P., Kutty R.K., Darrow R.M. et al. Changes in clusterin expression associated with light-induced retinal damage in rats. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 1994. 72(11-12). 499-503. doi: 10.1139/o94-067.

- Wong P., Ulyanova T., Organisciak D.T. et al. Expression of multiple forms of clusterin during light-induced retinal degeneration. Curr. Eye. Res. 2001. 23(3). 157-165. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.23.3.157.5463.

- Jomary C., Chatelain G., Michel D. et al. Effect of targeted expression of clusterin in photoreceptor cells on retinal development and differentiation. J. Cell. Sci. 1999. 112 (Pt 10). 1455-1464. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.10.1455.

- Aronow B.J., Lund S.D., Brown T.L. et al. Apolipoprotein J expression at fluid-tissue interfaces: potential role in barrier cytoprotection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993. 90(2). 725-729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.725.

- Kim Y.S., Kim Y.H., Cheon E.W. et al. Retinal expression of clusterin in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Brain Res. 2003. 976(1). 53-59. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02636-2.

- Martin P.M., Roon P., Van Ells T.K. et al. Death of retinal neurons in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004. 45(9). 3330-3336. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0247.

- Park S.-H., Park J.-W., Park S.-J. et al. Apoptotic death of photoreceptors in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat retina. Diabetologia. 2003. 46(9). 1260-1268. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1177-6.

- Holopigian K., Greenstein V.C., Seiple W. et al. Evidence for photoreceptor changes in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997. 38(11). 2355-2365. PMID: 9344359.

- Kim J.-H., Kim J.-H., Yu Y.-S. et al. Clusterin inhibits blood-retinal barrier breakdown in diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010. 51(3). 1659-1665. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3615.

- Suk S.А., Rykov S.O., Kyryliuk M.L. The role of cluste–rin as an antiapoptotic glial factor in the development of diabetic macular edema in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Archive of Ukrainian Ophthalmology. (Ukraine). 2019. 7(2). 30-35. https://doi.org/10.22141/2309-8147.7.2.2019.169686.

- Kyryliuk M.L., Suk S.А., Rykov S.O., Mogilevskyy S.Y. The role of clusterin in the development of diabetic macular edema in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Problems of Endocrine Pathology. (Ukraine). 2019. 69(3). 22-28. https://doi.org/10.21856/j-PEP.2019.3.03.

- Kyryliuk M.L., Suk S.A. The Content of Serum Clusterin in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema Depending on the Kind of Glucose Lowering Therapy. Journal of the Endocrine Society. April-May 2020. 4 (Issue Supplement 1). MON-668. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvaa046.049.

- Bringmann A., Wiedemann P. Müller glial cells in retinal disease. Ophthalmologica. 2012. 227. 1-19. http://doi.org/10.1159/ 000328979.

- Pannicke T., Iandiev I., Wurm A. et al. Diabetes alters osmotic swelling characteristics and membrane conductance of glial cells in rat retina. Diabetes. 2006. 55. 633-639. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-1349.

- Pelino C.J., Pizzimenti J.J. Medical Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. Modern Optometry. June 2019. 149(8). 90-99. https://modernod.com/articles/2019-june/medical-management-ofdiabe–tic-retinopathy.

- Gowda K., Zinnanti W.J., LaNoue K.F. The influence of dia–betes on glutamate metabolism in retinas. J. Neurochem. 2011. 117. 309-320. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07206.x.

- VanGuilder H.D., Brucklacher A.R., Patel K. et al. Diabetes downregulates presynaptic proteins and reduces basal synapsin 1 phosphorylation in rat retina. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008. 28. 1-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06322.x.

- Gastinger M.J., Kunselman A.R., Conboy E.E. et al. Dendrite remodeling and other abnormalities in the retinal ganglion cells of Ins2 Akita diabetic mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008. 49. 2635-2642. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0683.

- Bringmann A., Pannicke T., Grosche J. et al. Müller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog. Retin. Eye. Res. 2006. 25. 397-424. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.05.003.

- Bringmann A., Iandiev I., Pannicke T. et al. Cellular signaling and factors involved in Müller cell gliosis: neuroprotective and detrimental effects. Prog. Retin. Eye. Res. 2009. 28. 423-451. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.07.001.

- Gerhardinger C., Costa M.B., Coulombe M.C. et al. Expression of acute-phase response proteins in retinal Müller cells in diabetes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005. 46. 349-357. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0860.

- Simó R., Hernández C.; European Consortium for the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy (EUROCONDOR). Neurodegeneration in the diabetic eye: new insights and therapeutic perspectives. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014. 25. 23-33. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.09.005.

- Grigsby J.G., Cardona S.M., Pouw C.E. et al. The role of microglia in diabetic retinopathy. J. Ophthalmol. 2014. 2014. 705783. doi: 10.1155/2014/705783.

- Wang M., Ma W., Zhao L. et al. Adaptive Müller cell respon–ses to microglial activation mediate neuroprotection and coordinate inflammation in the retina. J. Neuroinflammation. 2011. 8. 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-8-173.

- Zeng H.Y., Green W.R., Tso M.O. Microglial activation in human diabetic retinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008. 126. 227-232. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.65.

- Cardona A., Pioro E.P., Sasse M.E. et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat. Neurosci. 2006. 9. 917-924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715.

- Imai T., Hieshima K., Haskell C. et al. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell. November 1997. 91(4). 521-30. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80438-9.

- Tuo J., Smith B.C., Bojanowski C.M. et al. The involvement of sequence variation and expression of CX3CR1 in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. FASEB J. 2004. 18. 1297-1299. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1862fje.

- Chan C.C., Tuo J., Bojanowski C.M. et al. Detection of CX3CR1 single nucleotide polymorphism and expression on archived eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Histol. Histopathol. 2005. 20. 857-863. doi: 10.14670/hh-20.857.

- Cardona S.M., Garcia J.A., Cardona A.E. The fine balance of chemokines during disease: trafficking, inflammation and homeostasis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013. 1013. 1-16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-426-5_1.

- Matsubara T., Ono T. Fractalkine-CX3CR1 axis regulates tumor cell cycle and deteriorates prognosis after radical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007. 95(3). 241-249. doi: 10.1002/jso.20642.

- Sawai H., Park Y.W., He X. et al. Fractalkine mediates T cell-dependent proliferation of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007. 56(10). 3215-3225. doi: 10.1002/art.22919.

- Perros F., Dorfmuller P., Souza R. et al. Fractalkine-induced smooth muscle cell proliferation in pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2007. 29(50). 937-943. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00104706.

- Garcia J.A., Pino P.A., Mizutani M. et al. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the fractalkine receptor during autoimmune inflammation. J. Immunol. 2013. 191. 1063-1072. 10.4049/jimmunol.1300040.

- Cardona S.M., Mendiola A.S., Yang Y.C. et al. Disruption of Fractalkine Signaling Leads to Microglial Activation and Neuronal Damage in the Diabetic Retina. ASN Neuro. 2015 Oct. 29. 7(5). 1759091415608204. doi: 10.1177/1759091415608204.

- Zabel M.K., Zhao L., Zhang Y. et al. Microglial phagocytosis and activation underlying photoreceptor degeneration is regulated by CX3CL1-CX3CR1 signaling in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Glia. 2016. 64. 1479-1491. doi: 10.1002/glia.23016.

- Mendiola A.S., Garza R., Cardona S.M. et al. Fractalkine Signaling Attenuates Perivascular Clustering of Microglia and Fibrinogen Leakage during Systemic Inflammation in Mouse Models of Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016. 10. 303. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00303.

- Kyryliuk M., Suk S., Rykov S., Mogilevskyy S. The role of fractalkine in the development of diabetic macular edema in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Endocrinology (Ukraine). 2019. 15(1). 10-15. https://doi.org/10.22141/2224-0721.15.1.2019.158686.

- Kyryliuk M., Suk S. The Content of Blood Chemokine Fractalkine in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Macular Edema Depending on The Type of Glucose Lowering Therapy. Journal of the Endocrine Society. November-December 2022. 6 (Issue Supplement_1). A334-A335. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvac150.694.

- Villeda S.A., Luo J., Mosher K.I et al. The aging systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature. 2011 Sep 1. 477(7362). 90-94. doi: 10.1038/nature10357.

- Cherry J.D., Stein T.D., Tripodis Y. et al. CCL11 is increased in the CNS in chronic traumatic encephalopathy but not in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2017. 12(9). e0185541017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185541.